Goodbye, USAID

Thoughts on Meaning, Solidarity and Purpose

The past couple of days my LinkedIn and social media have been filling up with testaments, memories, and reflections marking the official last day of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). USAID was a big part of my life and I’d like to share a little with you.

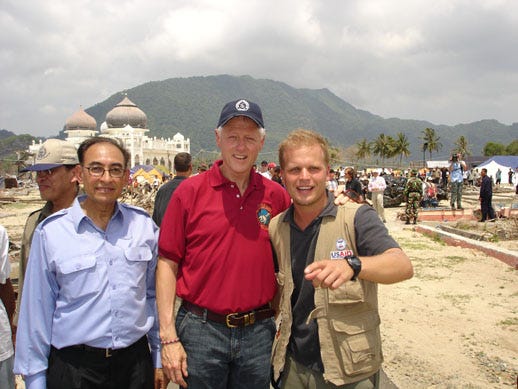

One of the tributes that stayed with me most actually surfaced back in April—from Dino Patti Djalal, the former Indonesian Ambassador to the United States and a former Vice Foreign Minister. He shared a video on his Facebook page that brought back a flood of memories from my years in Indonesia, just after the fall of Suharto’s New Order regime in 1998. I remembered working alongside extraordinary Indonesians to support the peace process in Aceh, foster reconciliation among religious and ethnic communities, rebuild after the devastation of the 2004 tsunami, train new parliamentarians, and help advance human rights. My years in Indonesia shaped me profoundly. They made me who I am today. I see the world as I do because of my life in Indonesia.

At its core, USAID was about ensuring that the margins did not define a person’s worth, trajectory, or possibilities. The agency and its partners worked with people others overlooked or excluded. It helped shift public discourse—and public policy—so that all people could shape the lives they envisioned, not just the ones they were permitted to have.

Many of my closest friends have been part of the USAID ecosystem—working directly for the agency, for implementing partners, or for national and regional organizations it supported. Some remained in those roles until just days ago; others have since moved on, carrying with them the values they honed and a deep commitment to human dignity. Across the world, these people worked in solidarity to help communities raise their voices, claim their rights, and shape the policies that affect their lives. USAID helped bring those on the periphery, the margins, into focus, and to push societies to recognize the full legitimacy, humanity, and potential of all their citizens.

In countless ways, people who had long been pushed aside—women and girls, people living with HIV, those with disabilities, so-called untouchable castes, ethnic and religious minorities, transgender people, Hijras, democrats and many others—found new tools and new allies to claim space, shape decisions, and push for change.

But let’s be clear: while many from the outside have helped, the credit for progress and change belongs to those individuals and communities themselves. It was their struggle, their voice, and their relentless effort that moved mountains. USAID offered support—financial, technical, and moral—to complement the vision, the leadership, and the victories that were theirs. And I do believe there is something deeply powerful about having a strong partner like USAID walk beside you, affirming your dignity and backing your efforts. After all, it takes a village.

Yes, we must continue to critique and dismantle the colonial legacies embedded in development assistance. Yes, we must challenge the patriarchal and extractive systems that reproduce inequality. But we must also acknowledge what was gained—freedoms earned, lives improved, and dignity affirmed.

Inequality persists. The global North—from development agencies to multilateral institutions to corporations and big tech—continues to wield disproportionate power. I will keep writing about this.

But for now, I just want to pause to remember and honor the change-makers, the doers, and the dreamers—those who turned USAID’s support into new realities for themselves and for future generations.

As I reflect on the history of USAID, I think about my own path into this work—a journey guided by conviction, curiosity, and the belief that development and progress is not about charity, but about solidarity. About people helping each other, with the right support at the right time, in the right ways.

John F. Kennedy created USAID in 1961 through the Foreign Assistance Act and Executive Order 10973. The agency expressed an emerging political belief: that the country’s security is tied to the prosperity and stability of others. It also tapped into a longstanding American culture of volunteerism and charitable engagement—only this time, scaled and formalized through government policy.

I came to these values long before I entered a USAID office. As a kid we used to send care packages to relatives in Poland. As a teenager I volunteered in church and community activities. And like many in my generation, I grew up watching the evening news on network television. The Bosnian War of the early 1990s was presented every evening. That’s when I first encountered terms like “ethnic cleansing,” “genocide,” and “internal displacement.” It was jarring. It also made me reflect on the accident of geography—that I wasn’t born behind the iron curtain, that my life could have been very different. Full of struggle, unfreedom and scarcity.

That realization shaped my sense of purpose. Even without possessing the language to describe it back then, I knew that helping others to build flourishing lives, on their own terms, was just something I had to do.

Little did I know where this was all going to take me, eventually leading to graduate school and, through a professor’s connection, to an intense meeting in 2000 with USAID’s then Mission Director for Indonesia. I still remember the grilling I got—especially from the desk officer who prepped me like I was heading into a final exam. But I was ready. I knew all about the ethno-religious conflict engulfing the country. I knew about its political economy. I’d learned Bahasa Indonesia and felt like I could contribute to something greater than me.

By October, I was in Jakarta as a USAID Democracy Fellow supporting the country’s transition away from authoritarianism. That was the start of a journey that lasted much longer than the 12 years I was with the agency—one that became far more than a job. It became my calling.

Its all coming back to me now

In the past few days, I’ve read moving reflections from friends, colleagues, and partners—people who dedicated years, even decades, to USAID, its mission and to diverse communities and people around the world. Floods of memories came back. Their words echo common themes: pride in the work, grief at its end, and fierce belief in the people and communities we served. Let me share two with you.

My friend and one of my inspirations at USAID, Nitin, put it this way upon ending a 26-year career with the agency:

We have faith that our work makes a difference, and that we leave the world a better place…[A] quote in the Netflix series “The Diplomat” where the Secretary of State said of Ambassador Hal Wyler: “All he ever wanted to do was find life altering solutions for a bunch of people he’s never met.” That’s the ethos through which my colleagues at USAID have lived our lives. In our hearts, we are public servants.

And from Shally, my very first colleague and officemate at USAID some 25 years ago, had this to say:

When I joined USAID in December 1998, I found my tribe -- others who, like me, had the audacity to think we could help catalyze social, political, and economic transformation in the world. Since then, I have focused most of my career on supporting other countries in their quest to build democratic institutions and protect human rights. Through local leaders, we helped communities and governments build their own brand of democratic governance. We strengthened service delivery and increased public access to clean water, education, electricity, health services, and their own legal rights. It has been a rocky road marked by moments of progress and then backsliding, which only illustrates how much more work needs to be done.

Now, Let’s Get to Work

The demise of USAID—and the ecosystem of financing, technical expertise, and solidarity it supported—is already being felt. But that can’t stop us. And the road ahead definitely won’t be easy.

In the weeks and months ahead, you’ll hear more from me in these pages. I’ll be writing about how this shift and other emerging challenges are affecting everything from tech governance to human rights, both broadly and in specific, tangible ways. I’ll share what I’m learning from grassroots actors—those whose decolonising approaches to progress continue to work toward a world where the margins do not define or confine us.

And I’ll keep doing what I can to name power, challenge it, and spotlight the tools, insights, and determination we need to build the world we want.

But today, I simply want to honor those who made USAID what it was.

To everyone who worked within the agency. To every partner, leader, activist, human rights defender, parliamentarian, journalist, lawyer, mental health campaigner, and democracy advocate. To all who labored—often quietly and against great odds—since 1961 to save more than 90 million lives, improve systems, and inspire change: your work has touched billions. And we are all better for it.

And to all who carry that torch forward in your own way, in your own place—I see you.

I salute you.

Trump's cut to all USAID by 30 September was the right call. So much waste and corruption. Good on DOGE