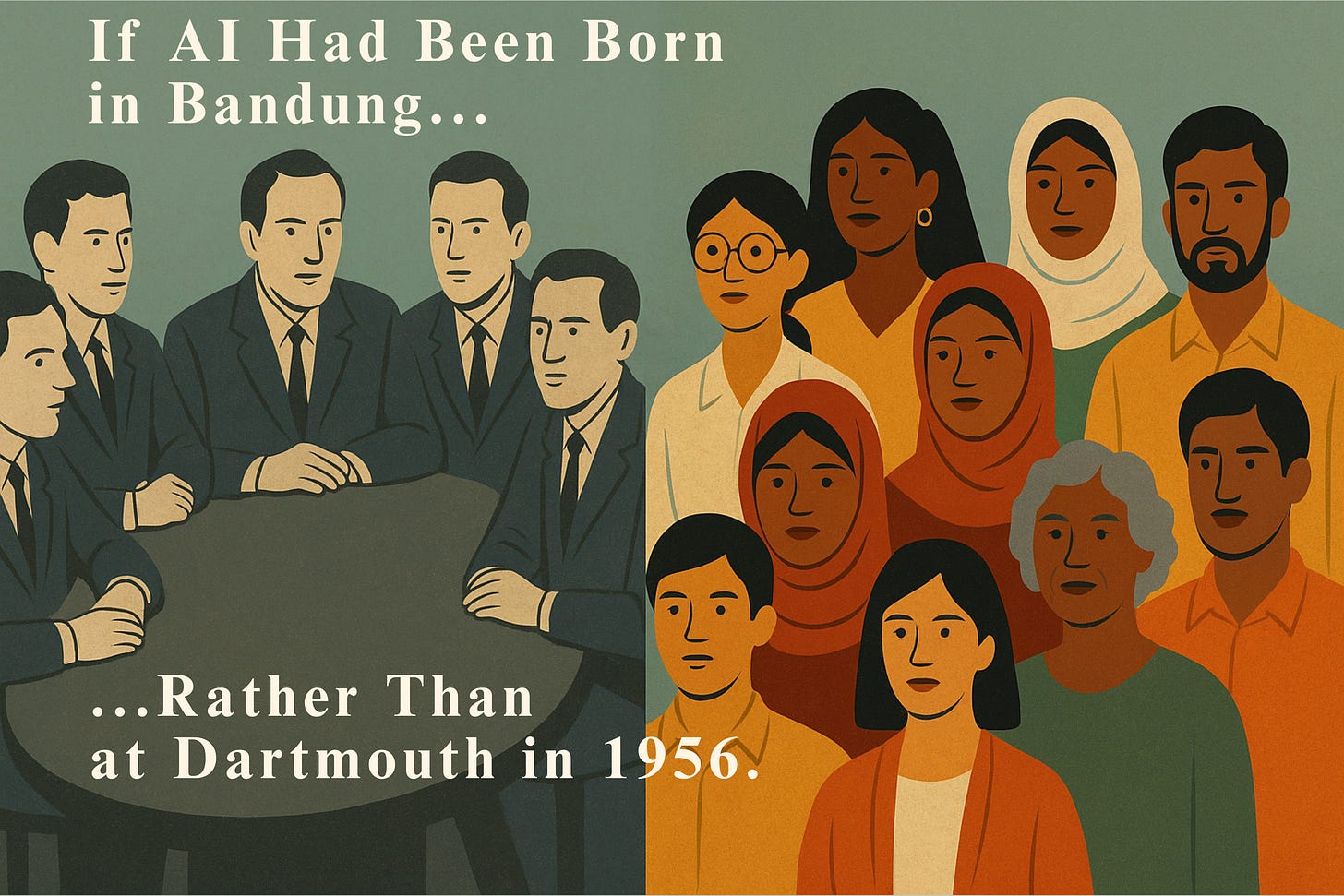

If AI Had Been Born in Bandung

Re‑imagining the 1956 Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence — and its implications for the world

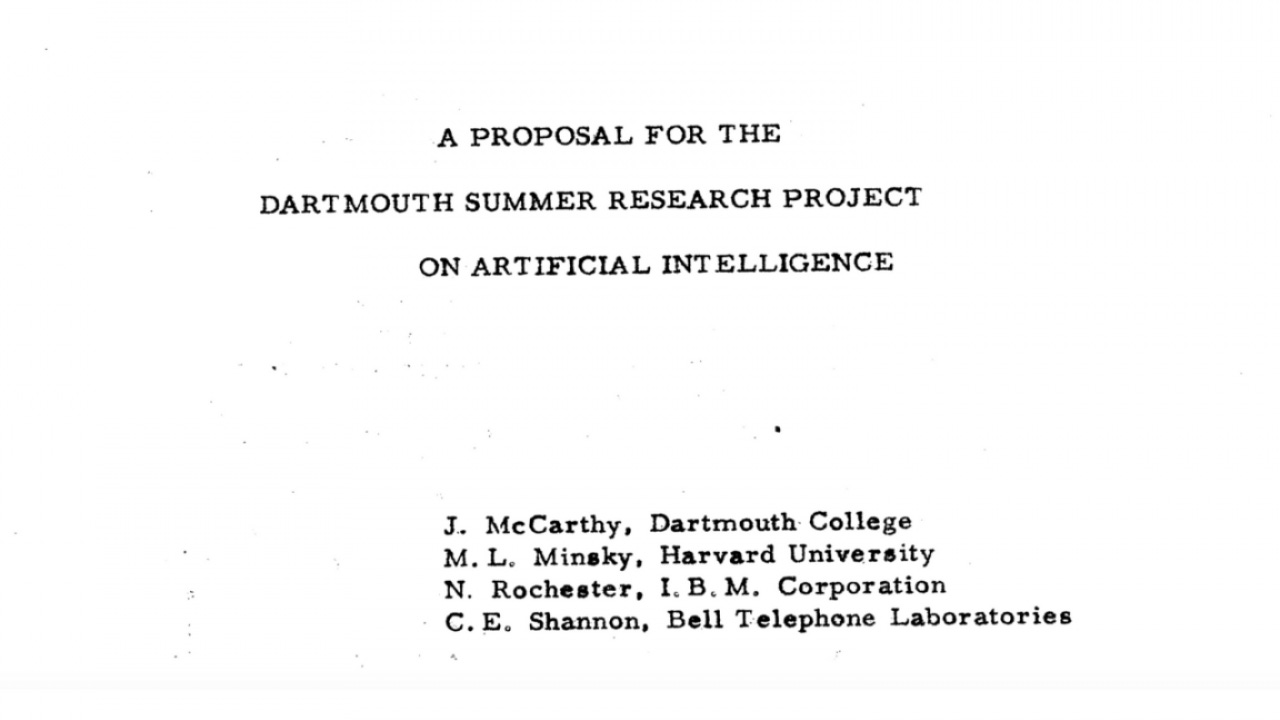

In the summer of 1956, a group of computer scientists and information theorists gathered at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, for the workshop formally titled the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. This is widely regarded as the founding moment of the field of artificial intelligence.

Their proposal declared: “Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.” A very powerful concept with very powerful implications, Indeed.

That origin story now underpins how many of us understand AI: a visionary technical moment designed to transform computation and cognition. I think that we can, and should, confront this story by reframing who imagined that historic moment and how — and ask the uncomfortable question: what if it has been different?

The Overlooked Context of the World in 1956

That moment at Dartmouth College did not happen in a vacuum. It came more than a decade after the United States, with the United Kingdom, had pursued the Manhattan Project — a massive, secretive scientific effort that resulted in the testing and deployment of the first atomic bombs, dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945. By 1956, the world had therefore already witnessed the devastating capacity of technologically advanced science when divorced from ethical and societal considerations.

Indeed, upon witnessing the destruction of the atomic weapons, J. Robert Oppenheimer famously said, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The scientists of the Manhattan Project — nearly all men — had demonstrated not just extraordinary ingenuity, but a chilling capacity for disciplined detachment that enabled them to unleash unimaginably violent forces on humankind while remaining largely insulated from the moral weight of their consequences. In the years that followed, American scientists, intellectuals, and policymakers became acutely aware of the existential stakes of frontier technologies.

And yet, just a decade later, when another group of men gathered in 1956 to speculate on what they called “artificial intelligence” — defined in their proposal as “making a machine behave in ways that would be called intelligent if a human were so behaving” — there is no evidence that ethical reflection or social accountability were central to their agenda. Even though their ambitious ideas were no less socially transformative compared to the recent atomic project – such considerations did not even warrant a discussion note on its margins.

Despite the recent memory of nuclear devastation, despite the clear demonstration of what powerful technologies could be developed by elite scientists, the foundational moment of AI appears largely indifferent to the societal, moral, and philosophical consequences it might unleash.

While I do suppose one may argue that contemplating such implications at that early stage would be an acceptable omission. However, this group of men were convinced they could solve the technical problem in one summer.

And besides, what is also striking is the context in which that omission occurred. This was well after the world had seen what scientific communities (that were hardly representative of broader societies) could create when working at the edge of knowledge without broader civic scrutiny (“I am become death.”). That summer at Dartmouth, the participants had every reason — historical, moral, and scientific — to consider societal implications of their ideas seriously. But as far as the record shows, it seems they did not.

At the same time these men were contemplating machine intelligence, vast parts of the world were picking up the pieces and trying to make sense of centuries of colonisation, oppression, and extraction. They were tilting toward liberation, self-determination, and moral reckoning.

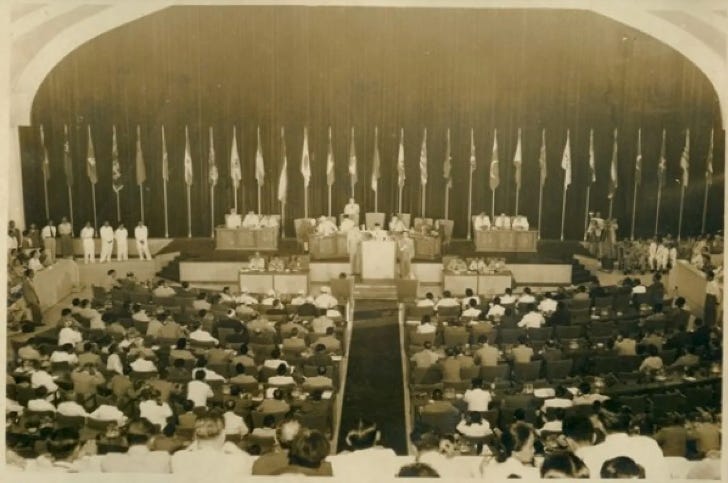

The 1955 Bandung Conference — held just one year earlier — brought together leaders of 29 recently decolonized nations of Asia and Africa, representing over half the world’s population, to chart a third way, outside Cold War binaries. They were attempting to throw off centuries of colonial domination and articulate a vision of peace, self-determination, economic cooperation and opposition to colonialism.

It remains a pivotal moment in the Global South’s assertion of political and cultural agency — and one that challenged the growing sense of geopolitical and intellectual dominance the United States was cultivating in the post-war era. In this sense, it seems reasonable to assume that American scientists wouldn’t feel the need to consider their objective of creating artificial intelligence with a grounding in power, justice or lived experience. Except that it really did matter.

In other words: that moment at Dartmouth College did not happen in a vacuum. It came after the second World War, in the era of the atomic bomb and Cold War escalation. While many parts of the world were undergoing decolonisation, rethinking power, autonomy and global structure. Where science and technology had not always been used for pro-social purposes.

Foundations and Founders Who Set the Tone

The Dartmouth workshop was convened by a cadre of men all working in American academic and research institutions — the kind of elite, technically‑oriented setting one associates with mid‑century American science. And they approached the workshop with incredible optimism, convinced they could solve the problem of artificial intelligence in that one summer break.

From today’s vantage point, the fact that the founding moment of AI was almost entirely male, white, U.S.‑based (and unreflective of global diversity) matters — not as a critique of their individual abilities, but as a critique of perspective and knowledge architecture.

The worldview that gets encoded into foundational research shapes what gets valued, gets left out, and how possible futures are imagined.

What If…?

Now let’s imagine something different.

Suppose that the seminal summer research workshop had been organised by women, by researchers and frontier scientists from the Global South, by gender and sexual minorities, by people whose lived experiences included exclusion, marginalisation, surveillance, and colonial legacies.

Suppose it took place not in Hanover, New Hampshire, but in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1956 at a time when newly‑independent nations were charting non‑aligned paths, seeking ways to harness scientific progress for all peoples. In a time and place where Indonesian President Soekarno was expressing concerns of the potential misuse of scientific progress, advocating for the ethical responsibilities that accompany scientific advancement, and calling for a more human-centric approach to scientific progress. [See Note 1 at bottom]

What might have been foundational in this “What If” context?

A research addendum that considered the range of potential implications of this new artificial intelligence on human flourishing, for all humanity, to share equitably.

Develop an early interest in ethics, justice and power dynamics in technological systems.

Initiate a culture surrounding scientific and technological innovation that equally emphasises philosophy, political economy, anthropology and social justice, as much as algorithmics and symbolic logic.

Focus advancements in new technology for inclusion, liberation, peace and care.

In the quest for making a machine that behaves in ways that would be called intelligent if a human were so behaving, demonstrate the need for a pipeline of scientific thinkers, researchers and leaders that is more inclusive of women, people from the Global Majority, marginalised communities and those whose voices and experiences are marginalised.

The list could, of course, go on.

What’s striking is not just what might have been imagined — but what was intentionally or unconsciously left out back then. The organisers of the Dartmouth summer research project believed that the technical challenges of machine intelligence could be solved that very summer. They approached the problem with the optimism (or hubris) characteristic of their time: confident that intelligence, once properly abstracted, could be replicated in machines. Yet for all their technical ambition, there is little evidence that they considered the broader societal, ethical, or political implications of creating such powerful technology.

In a world where inclusion, justice, and lived experience had been central to that foundational inquiry (to replicate human intelligence), AI might have begun on very different terms — not simply as a technical achievement, but as a tool for advancing human dignity, equity, and human flourishing.

How might the world look today?

We might now have tech design cultures where diversity is the default rather than the exception (and where American tech companies don’t blow-up diversity and inclusion efforts); where recommender systems and surveillance‑driven architectures are resisted (as anti-social and anti-people); where the default value of technology is human dignity (rather than profiteering from extraction and profit‑maximisation).

We will never know exactly what would have happened — history is messy, contingent and non‑linear — but we can reasonably guess that the technology landscape would look very different than it does today.

And we can definitely learn from that. And make changes.

From Dartmouth to Today: Tracing the Trajectory

I am not pointing fingers or disparaging at the organisers of the 1956 Dartmouth Summer Research Project; they were among America’s intellectual vanguard. They were also a product of their time — men educated and working in an era of deeply entrenched gender and racial hierarchies. In America of 1956, segregation was not just a memory but a lived reality; redlining was entrenched; women earned substantially less than men and held fewer of the credentials and opportunities that are now taken for granted.

Against this backdrop, it becomes less surprising that a field‑defining research workshop was led by men with similarly elite backgrounds, and that its foundational questions omitted attention to potential societal implications. But that doesn’t make it less problematic.

In the decades since, the rise of machine learning, user‑behaviour optimisation, social media algorithms, surveillance‑adtech and the privileging of profit over people have become dominant narratives in technology.

And I now find myself pondering this question: when the founding moments in technology omit or minimise considerations on impact on societies – especially questions of power, equity and justice – what inevitably gets designed out of the architecture of the future?

A “Bandung 2.AI” Moment: Rewriting the Future

I’ve written previously in these pages about a second Bandung‑style moment — “Bandung 2.ai” — a foundational gathering where the global majority is at the centre, not at the margins.

Here are some suggestions for how that could look and what it could prioritise:

Deciding seats at the table: Women, people from the Global Majority, marginalised communities (LGBTQ+, people with disabilities, ethnic/religious minorities) bring scientific rigor to innovation discussions and their peers from other disciplines have meaningful, sustained, substantive and equitable agency, not token representation.

Lived experience at the centre: people shaping tech should look, eat, believe, love, learn and live like the people whose lives will be shaped by the “innovations”. Their questions become design‑questions. It’s important we see ourselves in them, too.

Technology in the service of humanity: focusing on dignity (less on efficiency as the primary goal); on human flourishing (less on growth); on peace (not dominance).

Interdisciplinary grounding: An AI scientist today should study algorithm + ethics + political economy +philosophy + anthropology — building systems results in shaping and reshaping societies. Code impacts lives; those writing it need to understand the consequences.

Global infrastructures of solidarity: Research, design and deployment networks that centre formerly colonised geographies and people, cooperative models of exchange — not extractive global tech monopolies.

Final Thoughts

We cannot rewrite the past — the 1956 Dartmouth workshop stands as it was. But we can learn from what past contexts decided to leave out. We can make conscious choices around how to structure our knowledge ecosystems so that they incubate and nurture technology that serves us all, equally.