Techno-authoritarianism & Technocolonialism

Two Faces of Digital Power, Quietly Converging

A few days ago I was reading through a recent report from an NGO workshop a foundation hosted to inform their own tech policy support strategy. These CSO leaders discussed the full range of frontier tech issues: training and capacity-building needs, risks, concerns, fears, policy responses. The whole sha-bang.

My eyes quickly navigated to the section on techno-authoritarianism – which of course interested me very much as a digital rights advocate. Living in Southeast Asia, in the long shadow of China, civil society and citizens alike are increasingly concerned over techno-authoritarianism, also known as digital dictatorship.

What really caught my attention, however, was the absence of a section addressing the same issues and concerns relative to technocolonialism. I guess I just assumed there’d be a section on it, too. Why? Because the harms are just as real and citizens’ technological agency to resist is slipping.

But then it hit me: we haven’t normalised the conversation around technocolonialism yet — not in policy circles, not in multilateral forums, and certainly not in mainstream governance discourse. It’s rarely a conference headline, usually a margin note uttered from the audience.

And that’s a problem.

Once you step back and take a hard look, it becomes much clearer: techno-authoritarianism and technocolonialism share some deep structural similarities. The mechanisms may differ, but the patterns of harm, power, and control often overlap. And as we are seeing them play out today, sometimes they even reinforce each other.

In policy huddles and international meetings, we’ve certainly taken techno-authoritarianism seriously. We talk about how to prevent it, mitigate its impacts, and support those harmed by it. There’s even a burgeoning consensus among democracies: for example campaigns for red lines in AI, including the Ethical AI Alliance’s Clause 0 and the Global Call for Red Lines initiative. Local and regional organisations run campaigns against digital dictatorship, like those by Manushya Foundation. We see more calls for greater ecosystem collaboration.

But technocolonialism? Mostly a footnote, hardly discussed. Mostly, I think, because the North doesn’t fully grasp the lingering structural impacts of colonialism and Global Majority policymakers are worried about hurting the sensibilities of Northern tech companies (as if companies have feelings).

That needs to change.

We need to apply the same seriousness, the same energy, the same rigor, and the same policy imagination to technocolonialism as we are (rightfully) doing with techno-authoritarianism.

So where do we begin?

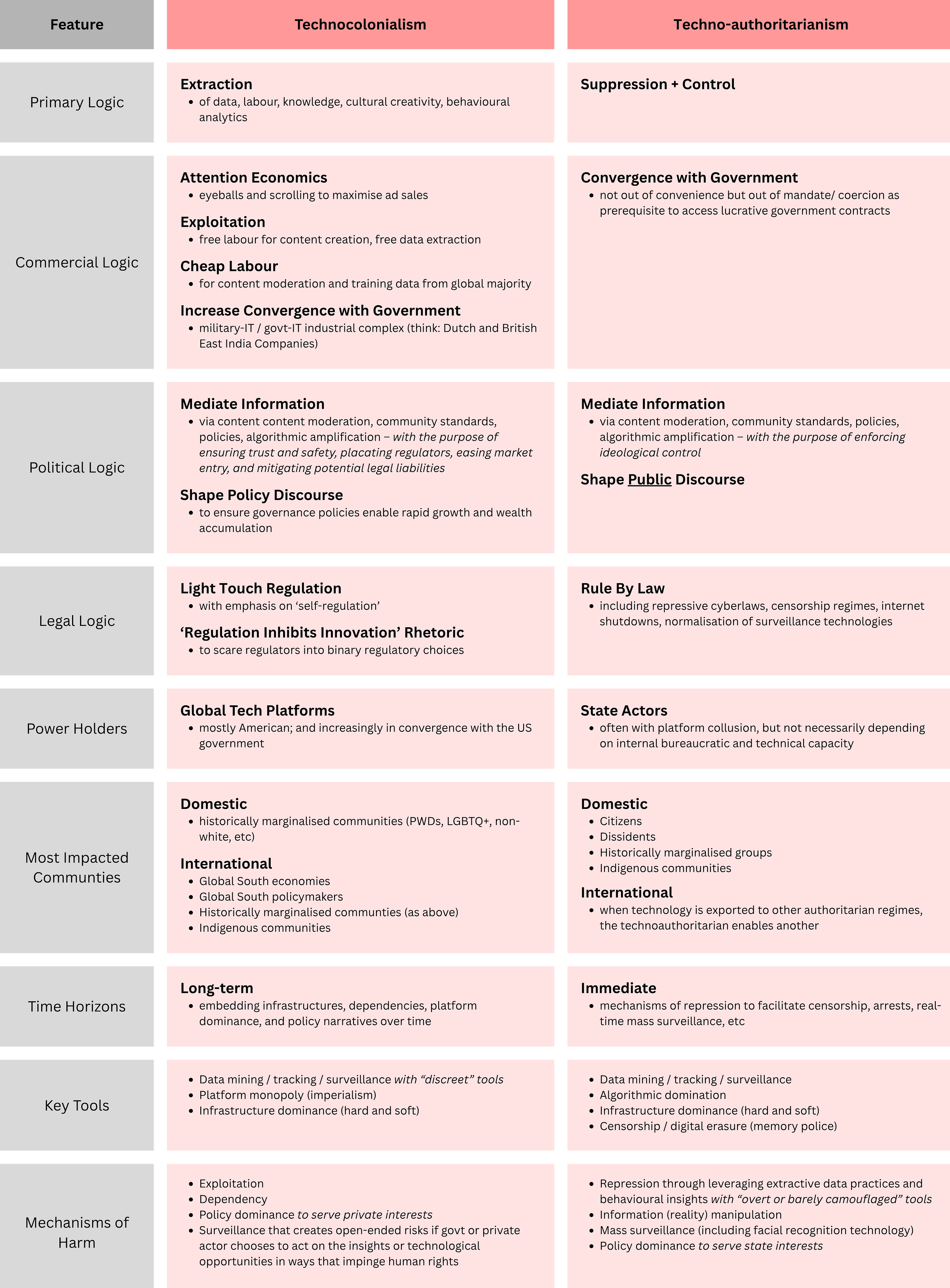

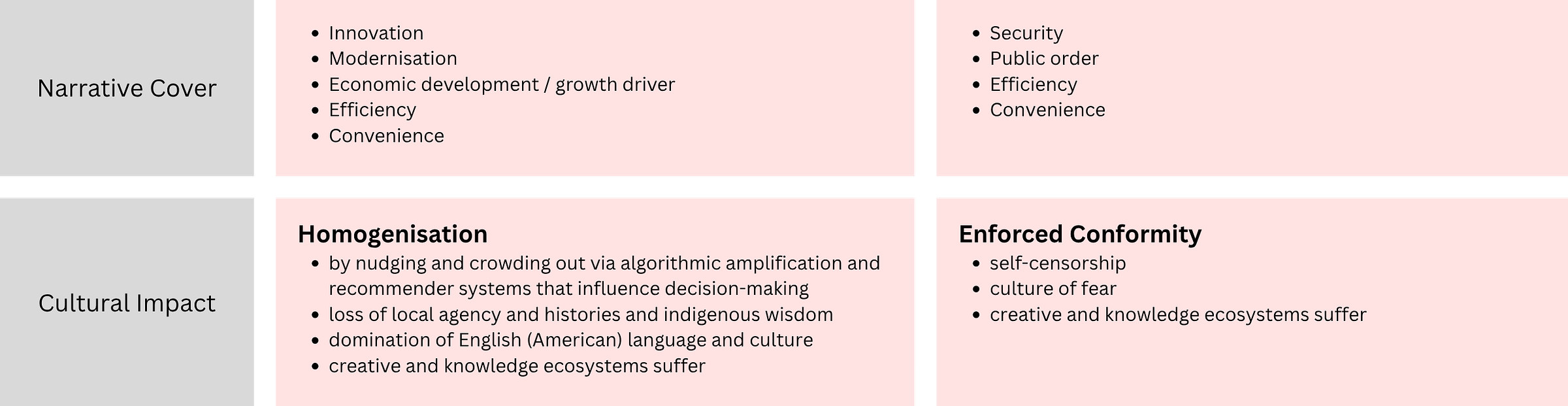

A good starting point is simply to compare them side by side. Rack and stack the features. What are the logics, actors, tools, and harms involved? What assumptions do we make about who benefits and who loses?

That’s what I’ve started to do in this table. It’s all really back of the envelope thinking at this point, so it’s not perfect. But it’s based on nearly 30 years of experience working on democratic governance, technology, and human rights across Asia. These are features I’ve seen developed and deployed.

As I was scribbling this table in my notebook, I had an oh-shit moment when it became clear that we aren’t facing two roads that diverge in the woods, as Robert Frost might say.

It turns out – they’re beginning to merge.

And that convergence should worry us all. Have a look.

Same, Same but Different(-ish)

Both appear to stem from different primary logics — one rooted in extraction and the other in suppression and control. However, the line separating them becomes increasingly blurred as we move through the various features in detail.

Technocolonialism historically hides behind the market logic of innovation and growth (never mind the old colonial logic of the centre knows best, and the periphery is to be extracted from and marketed to at the same time).

Meanwhile, techno-authoritarianism leans on state power and the rhetoric of security and order.

But in practice, these systems are becoming more interdependent, mutually reinforcing, and co-constitutive. (Just this week, this report came out documenting the complicity of American technology companies in China’s techno-authoritarianism.)

We see this convergence most clearly in the shared infrastructure of surveillance and control. The same data extraction tools developed for attention capture and monetisation now power predictive policing, behavioral tracking, and real-time repression using tools like instantaneous facial recognition.

Silicon Valley’s obsession with the lie that regulation inhibits innovation (debunked quite nicely by Anu Brandford here) has led to corporations pouring tens of millions of dollars into lobbying for “light-touch regulation.” The thing is, this then gives rise to “rule by law,” as the private sector’s self-regulation narrative conveniently softens the ground for authoritarian legal regimes while allowing the tech companies to further extract and surveil themselves.

Global tech platforms are also now becoming deeply entangled with state actors, both authoritarian and democratic (some increasingly nominally so), through military-tech alliances and the outsourcing of public functions to private code. Even the narrative covers are starting to rhyme: efficiency, order, modernization, and convenience are increasingly serving both commercial and authoritarian goals.

What emerges is not a tale of two separate roads, but what might be seen as an increasingly shared superhighway — built on infrastructures lacking democratic oversight, paved by global capital (itself extracted from the world’s peripheries), and increasingly policed by algorithmic gatekeepers. Whether under the banner of growth or control, both logics stifle dissenting voices, flatten culture, deepen dependency, and weaken democratic self-determination.

One of the things that troubles me most is this:

We still like to assume that Western tech corporations — and by extension the states that host them — are meaningfully bound by the rule of law, democratic oversight, and international human rights and humanitarian norms, laws and standards. We assume governments like the United States or EU member states will intervene to prevent the worst inclinations that private business enterprises might have.

We even developed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights with that very assumption in mind — that corporate harm can be shaped or restrained by governance and public accountability.

But that assumption seems to be crumbling, particularly as big tech becomes increasingly wealthy and powerful.

And especially as the American regime drifts further away from rights-protecting democracy and toward white nationalism — some say, fascism — we need to ask ourselves what happens when private tech empires and authoritarian states converge?

Convergence

Make no mistake: this cozying up is already happening.