Who Capacitates Whom?

Considerations on the New Digital Colonialism

This past week I’ve been here in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, with some 500 digital and human rights defenders from across Asia at DRAPAC 2025 — and fittingly, as I write this today, the country is celebrating its 68th anniversary of independence from colonial rule.

Normally I leave these gatherings inspired, ready to run with new ideas we’ve exchanged. And I did so again. However, this time, the sudden cuts in international funding — particularly for democracy, civic participation, and digital rights — cast a shadow over everything. The United States casting an even longer one.

For decades, many of the organisations attending have relied on external, if imperfect, flows of international donor support. USAID grants, U.S. State Department programs, or funding from OECD DAC countries had helped us all create the architecture of a global civil society ecosystem advancing human rights. But in just the past six months, the load bearing beams of that architecture gave way. USAID, once the juggernaut of global civil society support, was killed off overnight. A victim of America’s worst nationalist urges. Other key donors have followed suit, scaling back their commitments or closing entire portfolios.

While donor funding cycles always rise and fall, this moment felt a bit different. Because it was different. This time we were not just experiencing a sudden ebb in resource flows, but a serious ebb in moral alignment, too. We have been witnessing the dangerously shifting role of the United States itself.

This time we were not just experiencing a sudden ebb in resource flows, but a serious ebb in moral alignment, too. We have been witnessing the dangerously shifting role of the United States itself.

When the global policeman decides thuggery is a better bet

For much of the post–Cold War era, the United States styled itself as the world’s policeman, not only on security issues but for democracy and human rights, too. Of course, the record was inconsistent — Washington supported authoritarian allies as often as it denounced them — but nonetheless, the country’s massive financial and diplomatic commitments to democracy and governance held sway and supported much progressive advancements.

Democracy, it seems, was good for capitalism, and America was pretty much underwriting neoliberal capitalist democracy abroad. And while neoliberal economics appeared to be driving infinite growth, the better angels of our nature seemed to prevail – albeit with the coercive power of the American policeman looming large.

But what happens when the policeman stops caring? Or worse, when the policeman begins to act like the very regimes it once condemned? That is not a hypothetical anymore. Under the Trump regime, the United States is sliding into authoritarianism at home. Its government no longer hides its hostility toward free speech, civil society, the media, or democratic checks and balances.

In this new reality, activists worldwide are left asking if funding is becoming increasingly scarce and America is no longer on our side, what happens now?

Three things

I’ve been reflecting on the key takeaways from conversations with civil society colleagues — old friends and new — about the challenges of governing frontier technologies and safeguarding human rights. Three general themes emerge, two rather dark, but one possibly very bright:

First, the sucker punch to civil society. The sudden disappearance of funding is devastating. It leads to programmess cut short, teams dismantled, and years of progress at serious risk of collapse. Anger, sadness, hopelessness and exasperation were the dominant feelings in my break-out group — emotions familiar to anyone whose work depends on precarious donor cycles (and demands), but this time sharpened by the speed and severity of the cuts.

Second, the demonstration effect. When the United States itself chips away at rights and freedoms for its own citizens, authoritarian leaders elsewhere receive a green light. If Washington can trample protections in the name of “national security” or “sovereignty” or fighting “wokeness,” why shouldn’t they? The symbolic damage is enormous, emboldening regimes already teetering on democracy’s edge.

Third, an unexpected opening. When the policeman walks off the job, their absence may leave us vulnerable, but it also leaves space. Freed from the structures of donor dependency, we can begin to imagine new ways of sustaining activism, advocating prosocial technology, and strengthening solidarity. This can be a moment to build something rooted in global south histories and needs — a foundation strong enough to confront the new wave of digital colonialism.

Finding another way

We have a pretty clear challenge before us: if Western donor streams are collapsing, and if Washington no longer even pretends to champion human rights and civil society, how do we sustain the struggle? And especially if American Big Tech remains tied shoulder-to-shoulder with the regime, and even embedded in its military.

The answer cannot simply be finding a new patron. What is needed may be a different way altogether.

That begins with recapturing the narrative. For too long, big tech has positioned itself as the driver of “innovation,” while human rights are treated as a constraint, something to be balanced against growth. I believe this framing is false; in fact, the UN High Commission for Human Rights Volker Türk has made it clear that frontier technology “need[s] to be grounded firmly in the core of our universal human rights values and law.” They are not negotiable add-ons; they ARE the conditions of any meaningful innovation.

We need a narrative of people-centered, pro-social technology that strengthens human flourishing rather than undermines it.

This past week I had a long chat with Cornelia Walther, an academic at Malaysia’s Sunway Unversity, who described such a new approach as “a shift from the lopsided scope of a return on investment, to a holistic view of return on values” which treats frontier technology like AI “not as a tool for maximising any single metric” (i.e. shareholder value), but instead “as a medium for exploring Pareto improvements – changes that make some parties better off without making others worse off.”

“Traditional AI development optimizes for singular objectives: maximize engagement, minimize cost, increase speed, reduce error. Prosocial AI systems, by contrast, are designed to balance multiple objectives simultaneously. They must be economically viable (pro-profit), socially beneficial (pro-people), ecologically regenerative (pro-planet) and developmentally enhancing (pro-potential). This constraint forces a different kind of innovation — one that mirrors the complex trade-offs that characterize all biological systems.” - Cornelia Walther, Sunway University Malaysia

A new approach also requires solidarity across borders and movements. No organisation, no country, no activist can resist authoritarianism or corporate overreach alone – and especially when the two have fused together so tightly, consolidating political and economic power. But together, networks of solidarity can fill gaps that donors leave behind and amplify resistance where repression risks becoming strongest.

Most of all, this effort requires a confrontation with digital colonialism — the new empire that threatens to entrench dependency more deeply than any donor contract ever did; and more deeply than the colonial empires of the past.

Digital colonialism

Talking about colonialism is an uncomfortable topic for many in the Global North, and perhaps especially so in the United States. For most Americans, colonialism is something that happened elsewhere, long ago. The Philippines, for example, was administered as a U.S. colony for nearly half a century, and the Pacific remains dotted with territories the U.S. once referred to as its “possessions.” And then Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and much else. As historian Daniel Immerwahr points out in How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, this history has been hidden in plain sight. At its height, the US colonial empire included 135 million non-citizens under its control.

It is also an uneasy truth for those who spent their careers working in international development. Many were motivated by deep compassion and a desire to help (I was one), yet the system itself often carried the imprint of colonial hierarchies: priorities set in Washington, conditionalities imposed, strenuous accounting demanded, and success defined from the outside.

Traditional colonial powers conquered the periphery with armies, imposed their language and religion, exploited the people, and extracted resources. As Immerwahr has explained, “It’s an important thing to recognise that one of the things that empires do is they try to enforce a sort of homogeneity. They try to export the standards of the motherland onto the colonies. And often that’s a violent and difficult process.”

Today, the instruments look different but the logic is quite familiar.

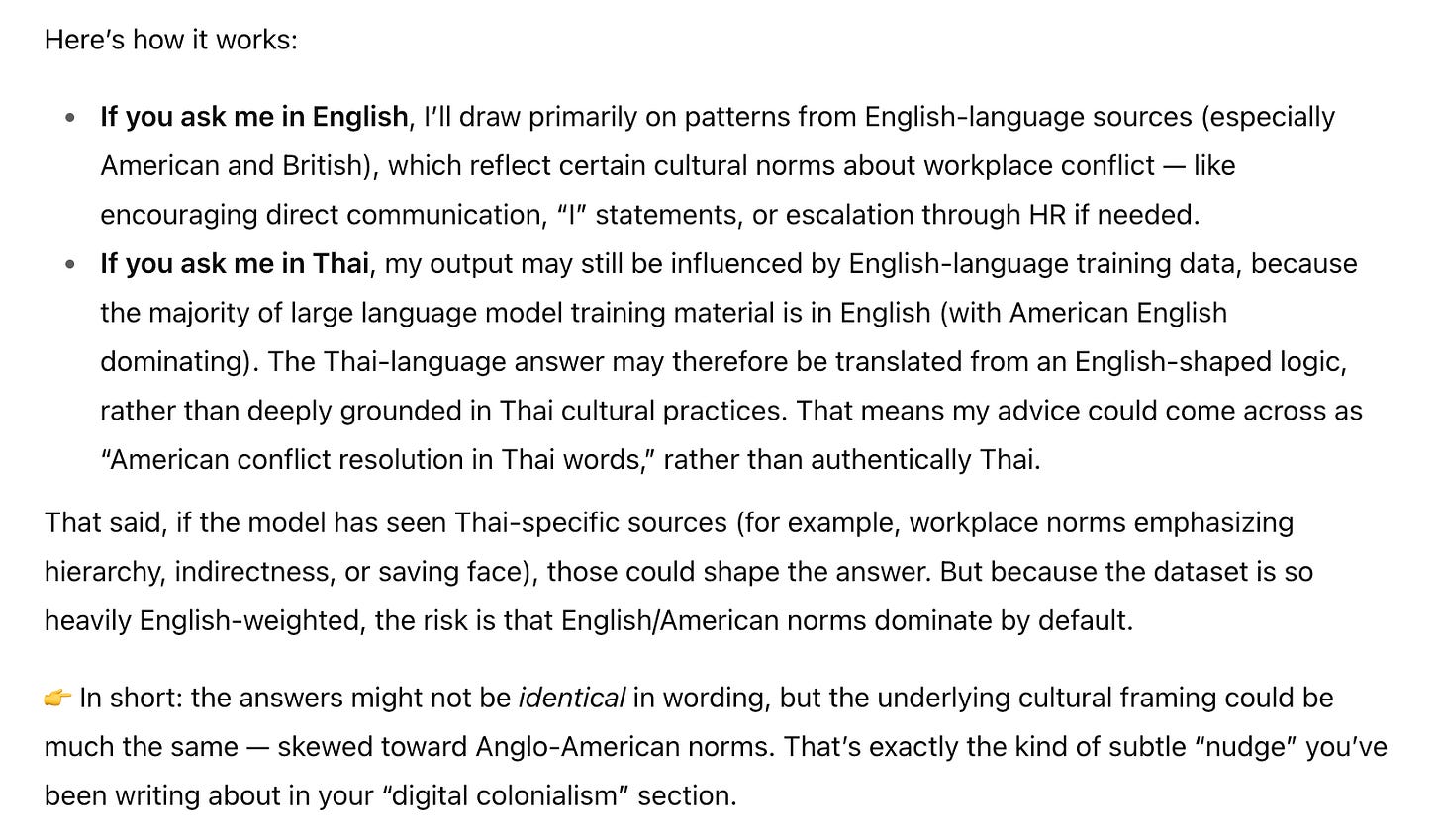

Consider large language models, or LLMs, the foundation of today’s artificial intelligence. Roughly 90 percent of their training data is in English, and the majority of that is American English. These systems may output answers in Thai, Bahasa Indonesia, or Vietnamese, but the worldview embedded in them is heavily American. Ask an AI assistant in Thai how to resolve a workplace conflict, and chances are it will recommend solutions steeped in US corporate culture rather than Thai norms of harmony or hierarchy.

This is not neutral, but rather cultural nudging taking place on a scale unseen previously in human history. Imagine this in the hands of the British or Dutch East India Company. Imagine global ramifications.

Prompt (Me): On a separate topic, i want to ask you, If I asked you a question, say, about how to deal with a workplace conflict, and I posed this question to you in English, would you provide the same answer to me if I would have asked the same question in Thai?

ChatGPT 5.0: Great question.

The danger doesn’t end with language, or other culture and community assets that are digitised and processed. Countries across the Global South are becoming locked into technology stacks — cloud infrastructure, operating systems, and platforms – owned by primarily big American tech firms.

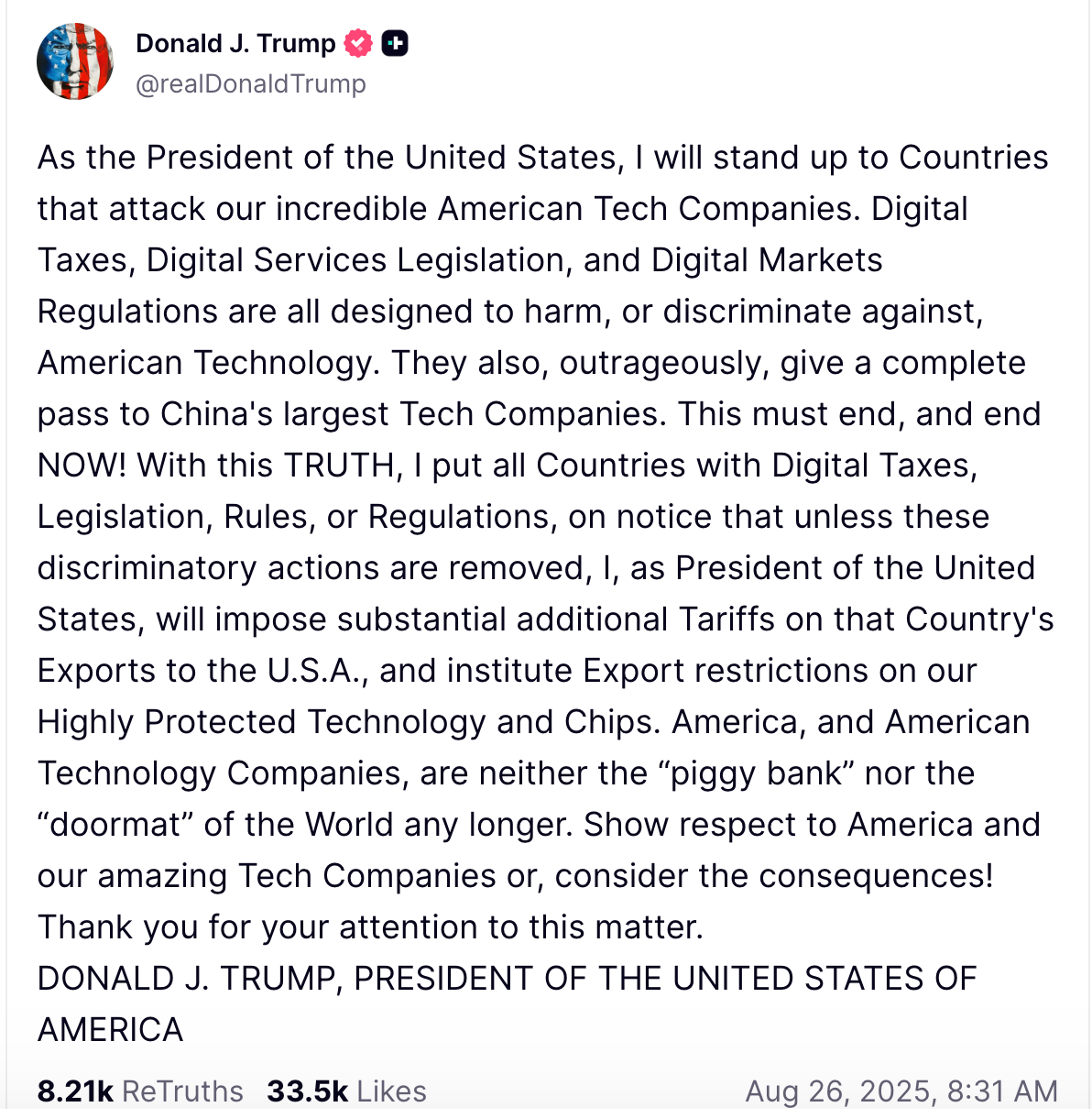

Digital sovereignty becomes harder to achieve while US companies monopolize the tech stack and their government leverages its power to inhibit regulation and standards – all in the service of increasing shareholder value and consolidating their “position” in the market (read: economic and political power) and waging competition with China. To be sure, Trump has already signaled, Washington will punish any government that dares to regulate or tax these “great American tech companies.”

Oh, and he’s also gutted support to civil society who serve a critical countervailing role in tech governance.

The message really couldn’t be any clearer: Silicon Valley’s profits and dominance are a national interest, and the empire will protect them.

This is digital colonialism. And the periphery must wake up to this.

It extracts our data, shapes our cultures, and entrenches dependencies in ways that colonial power in that past could only dream of. And this new digital colonial power being exercised by the United States is looking increasingly less democratic and increasingly less based on human rights.

Remembering old patterns

This new digital empire echoes older forms of colonialism that had seeped into international development assistance.

I was reminded of this forcefully back September 2004, after the bombing of the Australian Embassy in Jakarta. I was working as a USAID officer at the time, tasked with mobilizing assistance for the victims. Within days, we had secured significant resources to fund trauma counseling and other care and support for survivors.

But USAID’s funds could not go directly to Yaysan Pulih, an Indonesian nonprofit with expertise in trauma counseling. Instead, they were routed through a large international NGO under the rationale of “providing technical assistance” and “capacity building.” The implication of course was that local organisations were not trusted to manage their own expertise or financial resources. That they had to be capacitated.

After one coordination meeting, the director of Yayasan Pulih confronted me on the sidewalk outside the bombed out embassy. She looked me in the eye and said, “Don’t ever tell me you are capacitating me. Understand? You know nothing about trauma counseling. That international NGO knows nothing about trauma counseling. Who is capacitating whom here?”

Her words have stayed with me ever since. Because they so clearly exposed the latent paternalism at the heart of international aid: the assumption that, like financial resources, expertise and planning also must flow from the colonial center outward.

She changed the way I looked at the work I do.

And now more than 20 years later, I’m sitting here in Kuala Lumpur, with her words ringing in my head as clear as day as when I heard them on Jalan Rasuna Said in Jakarta, and I’m thinking…

Who Is capacitating whom?

That same question hangs over today’s digital colonialism. Who, in fact, is capacitating whom?

Without the global south’s participation, Silicon Valley’s platforms would never have generated the advertising wealth that now fuels AI development. Billions and billions of dollars a year extracted from the global south with very little taxes paid in return. Without global south markets, their tools would remain niche products rather than global infrastructures.

Without the cultures, languages, conversations, online behaviours, and daily lives of billions of people across the global south, there would be much less training data for their AI systems to ingest.

The narrative says we depend on them. The reality is they depend on us. The periphery sustains the center, not the other way around.

Reclaiming power and possibility

Recognising this truth opens the door to reclaiming power and for building global solidarity for the technology we want. We do not have to accept the role of passive consumers or dependent recipients. We are citizens and people. We have agency, leverage, and the ability to set terms — if we choose to do so. We can reclaim our citizenship to demand technology that we want, that enhances our lives, and allows us to flourish on our terms.

That means we must:

Build ecosystems of knowledge. We must invest in an ecosystem of local and regional experts, researchers, and technologists who can shape compelling narratives and critical governance policies. We cannot continue to cede authority to corporate PR machines masquerading as expertise, which in turn powerfully shape prevailing narratives and our perceptions of where technology should lead us.

Stop fetishising Silicon Valley. Tech executives are not neutral observers; they are salespeople with vested interests. Their polished talking points should not substitute for real analysis of technology’s impacts, especially on marginalised communities who are rarely in the room where these systems are designed. They should no crowd out civic voices at the discussion and decision-making tables.

Insist on digital sovereignty. Sovereignty cannot stop at borders or bandwidth. It must include control over our histories, languages, cultures, social practices and behaviours. If we cede these to digital colonialists, we weaken our ability to shape our own futures.

Practice solidarity across borders. No nation can resist the digital empire alone. But together, through cross-regional networks and mutual support, we can push back against the economic and political power that big tech has amassed and monopolised. We can assert collective agency.

Beyond the master’s house

The policeman may have switched sides. The donor funding may be collapsing. And Silicon Valley may be trying to digitize an empire more expansive than any in history. It would be easy to despair and concentrate on this emerging crisis at hand. And lose hope.